An ancient quasar has emitted radio jets longer than our Galaxy.

Supermassive black holes, believed to be located at the centers of nearly all galaxies, form an accretion disk from the surrounding matter. As matter falls from these accretion disks into the black holes, some of it is expelled from both poles of these cosmic "monsters," creating narrow jets of plasma, also known as jets. They erupt from the vicinity of black holes at nearly the speed of light, and their lengths can extend for many light-years.

For instance, the previously discovered astrophysical structure Porphyrian — two streams of charged particles stretching over 23 million light-years — can influence the distribution of matter and magnetic fields in the so-called cosmic web.

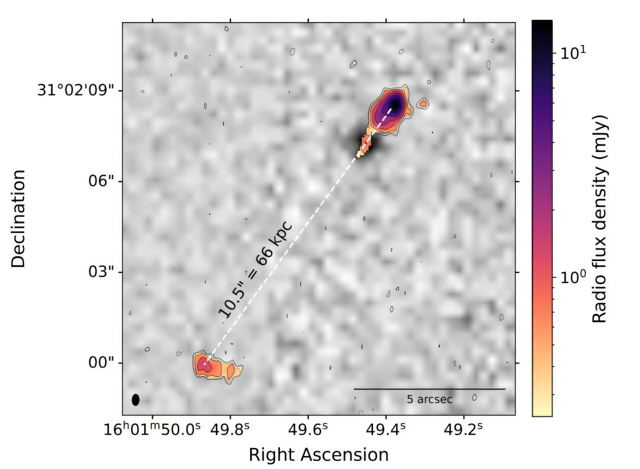

However, results from a new study, presented on the Cornell University preprint server (USA), revealed that the extremely bright quasar J1601+3102, which astronomers observe as it was approximately 12.5 billion years ago, emits powerful radio jets extending over 200,000 light-years.

Previously, such a phenomenon was not considered possible: before this discovery, astronomers believed that the dense relic radiation (a uniform thermal radiation filling the universe, which originated during the epoch of primordial hydrogen recombination) at high redshifts drained energy from the jets and prevented their further expansion from the parent galaxies.

Yet the two radio jets — massive energy and particle outflows — on either side of the central black hole of the quasar, observed at a frequency of 144 MHz with sub-second resolution using the LOFAR (Low Frequency Array) radio telescope, overcame this loss.

An international research team led by astronomer Anniek Joan Gloudemans from the Gemini Observatory proposed that the reason for the observed phenomenon is that environmental conditions during the quasar's formation were favorable, allowing it to avoid a colossal loss of energy. Notably, J1601+3102 formed in the universe when it was less than a billion years old.

“It was thought that such extended radio jets in the early universe were suppressed due to interactions with relic radiation. However, we now observe a jet that has reached enormous sizes. This discovery challenges our understanding of how these structures form,” explained Gloudemans.

To study the ultraviolet spectrum of the quasar and estimate the mass of its central supermassive black hole, the team of scientists used the Gemini Near-Infrared Spectrograph (GNIRS).

The results showed that the mass of the cosmic "monster" was about 450 million times that of our Sun — a relatively modest size compared to other known distant quasars. This, according to astronomers, suggests that particularly supermassive black holes are not a necessary condition for the formation of powerful jets.

Moreover, this unusual quasar was accreting matter at nearly half of the Eddington limit (a threshold related to the maximum luminosity of a black hole's accretion disk and the rate of matter absorption). This indicates that the black hole was growing extremely rapidly.

The discovery, according to its authors, not only enhances our understanding of galaxy evolution and black hole growth in the early universe but may also lead to a revision of models that predict limited radio jet activity due to interactions with relic radiation.

The research group's findings also do not rule out a more significant role for the jets in shaping the early universe. Further observations are planned to be conducted by astronomers using next-generation radio telescopes, such as the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), which will allow for unprecedented detail in studying the "childhood" of the universe.