Nearly three billion years ago, volcanoes erupted on the far side of the Moon.

The first images of the hidden side of the Moon, captured by the Soviet station "Luna-3," were revealed to the world in October 1959. These images enabled the creation of the first map of this previously unknown region and the first lunar globe.

It is noteworthy that the side of the satellite visible from Earth has a significantly lower number of seas due to the thick crust, while the seas are extensive dark areas (and have no relation to water). Previously, Naked Science reported on the analyzed soil samples collected during the "Chang'e-5" mission.

After the return capsule of "Chang'e-6" landed in Inner Mongolia with just over 1.9 kilograms of rock onboard, a team of scientists led by Zexian Cui and Qing Yang from the Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, employed radioisotope dating and mass spectrometry methods to accurately determine the age of the basalt found, which was 2.83 billion years.

In particular, isotopic analysis of strontium (Sr), neodymium (Nd), and lead (Pb) revealed that the magma that formed the basalt originated from a source depleted in incompatible elements within the Moon's mantle (i.e., elements that do not become part of the main minerals when magma crystallizes and remain in the melt) and contained almost no so-called KREEP component — potassium (K), rare earth elements (REE), and phosphorus (P).

This is significant because the latter are considered a key factor in sustaining prolonged volcanic activity due to radiogenic heat (on Earth, this heat is generated by the decay of radioactive elements in its interior). The KREEP component, rich in radioactive elements (K, Th, U), contributes to additional heating of the mantle and, consequently, volcanism. Its absence may have led to reduced volcanic activity on the far side of the Moon.

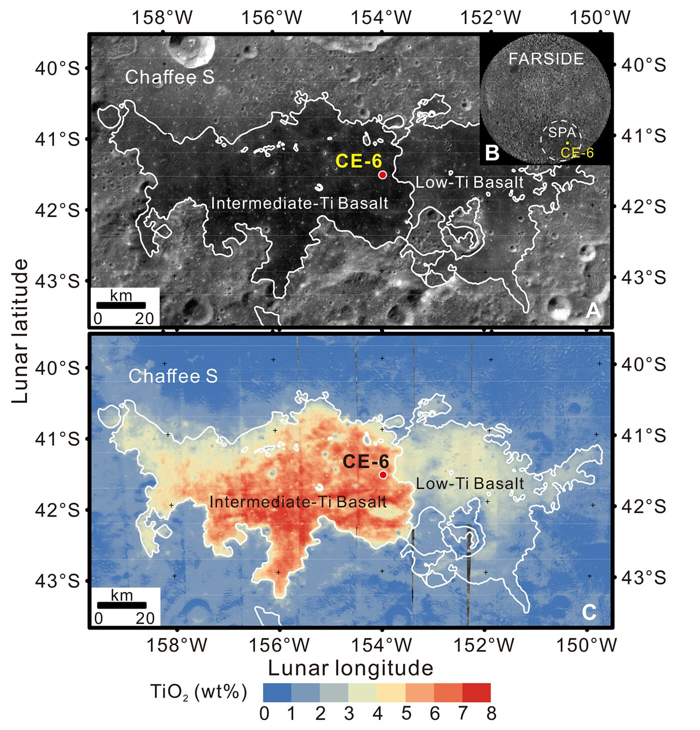

For this reason, the lack of the KREEP component in the studied samples has been linked to the redistribution of material to the Earth-facing side of the Moon due to the impact that formed the South Pole–Aitken basin. Thus, the findings of the research presented in the journal Science explain why volcanism on the far side of the Moon was not as prevalent as on its visible side.

The efforts made by the team of scientists from China have shown that volcanic activity on the Moon lasted longer than previously thought, extending beyond the first several hundred million years after its formation.

Knowing the precise age of the lunar rock brought back to Earth (2.83 billion years) will also enhance dating methods for various regions on the surface of our planet's satellite. This can be achieved by analyzing the density of impact craters, which, in turn, will help to complete the chronological picture of the Moon's bombardment by meteoroids and asteroids.